US monetary policy to remain loose, Syria tensions overhyped, most populist Indian bills priced in. Indian inventory growth is flat, while the J-curve should show up soon.

We are not quite at the bottom, but we are nearing it. The rupee has fallen and the dollar has risen rather dramatically - no need to retell that story, just see the graph below - but the equity markets have held up relatively well (at least in rupee terms). This is not a recommendation to start catching falling knives. This is a call to remain alert and consider becoming less bearish.

Why? Five reasons - three factors that have been exaggerated, and two that have been underplayed:

1. The “Fed stopping the easy money” theme has been overdone. Yes, there has been a recovery in the US, but it is slowing. Consider some facts. Personal/consumer spending in the US was up just 0.1% in July compared to June (that is, 1.2-1.3% annualized). The 0.1% number was the lowest since April. What also rose just 0.1% from June to July? American prices (core price increase, excluding food and energy, was also 0.1%). Therefore, “spot” inflation (annualizing) is also around 1.2%. This number too - along with growth estimates - has come down compared to last month. What this means is that the Fed is now more likely than it was a couple of months ago to be more dovish on the margin. The likely replacement candidates for Bernanke - be it Janet Yellen or Lawrence Summers - are both dovish i.e. for easy/loose monetary policy (none of them are going to be a hawk like Paul Volcker, not that one is needed). Yes, Janet Yellen maybe more dovish than Larry Summers, but that is splitting hairs. The story is a bit different in Europe and Japan. Across the Atlantic from New York, UK consumer confidence data is higher and EU unemployment is marginally lower. In Japan too, Abenomics has finally got inflation to 0.7% (core CPI). But here is the thing - besides a couple of LTROs (Long Term Refinancing Operations) and other measures in EU, and the recent rush of QE from Tokyo - the global markets (at any rate the Indian one) are still predominantly focused on the Fed. This is not to underestimate the other two rich-world entities, but even there any tightening is implausible for the near future – especially in Europe.

2. Any serious, sustained invasion of Syria has a very low probability - and hence oil prices are probably near their short-term peaks. Even a one-off attack flaring up into some serious international crisis is unlikely. After the war-weary UK parliament, across party lines, denying their PM David Cameron the mandate to attack Syria, the US President Barack Obama just this weekend has also thought about his remaining anti-war, anti-interventionist street-cred and decided to go to the American House and Senate for authorization. The chances of those two august gatherings of the American representatives to quickly and decisively agree about anything is rather low - even on apple pie, it seems (motherhood? no chance). Russia and China have the UN veto, Israel does not want any protracted conflagration, and neither does Saudi Arabia or especially Iran. It will be made sure that just enough is done so that the American President can enter the coming mid-term elections as a “statesman”. In any case all this is relevant, especially for India, because it impacts the oil price (nobody cares about the Just War theory). Since the penultimate stage to Armageddon was already priced in, we all can breathe free. Moreover, there remains structural reasons to be short oil (in USD). Demand is peaking, while supply has unsurprisingly continued to surprise. Sub-100 prices on Brent is plausible by the end of the year.

3. The great socialist republic of India is lurching towards two very enlightened acts on Food Security (FSB) and Land Acquisition (LAB). [“Act” here refers to pretense, not a piece of law] With the Minimum Support Prices (MSP) at which the Food Corporation of India (FCI) buys some grains, especially cereals, we are at a situation that many wheat farmers in India would first sell their produce to the central government at 14 Rs/kg, and then buy some of it back at Rs. 3/kg. It boggles the mind to see this kind of centralized waste and institutionalized corruption, but it does not really surprise. Instead of supporting food stamps and cash transfers, and allowing states to experiment, we have put on an additional gigantic fiscal obligation just when the rupee was panicking, and the central bank had no good option. Similarly, LAB fixes prices for land even for fully consensual decisions - and is going to lead to much more paperwork. But the only silver lining here is that the markets have already priced these scenarios, and any more large populist projects with substantial fiscal expenditures are unlikely over the next few months, though of course one can never be sure. Moreover, the FSB does not go towards implementation phase right away. The Indian fiscal deficit situation is being partially ameliorated by consistently raising petrol and diesel prices, even if under-recoveries remain. Moreover, as shown later – the Indian debt to GDP ratio has been falling/stabilizing for sometime now. The same inflation that is so politically toxic and economically inefficient can be fiscally wonderful – as it reduces the real value of the stock of government debt.

4. Indian inventory growth has collapsed, along with industrial production. The June 2013 year-on-year Inventory growth was a negative 0.4% in real terms, and 5.18% in nominal terms, which suggests that this downturn cannot last much longer. It also shows that we are in a much worse situation perhaps than some other indicators suggest. Corporate investment as a % of GDP was 10.6% in 2011-12 and has almost certainly fallen much below (in 2003-04 it was 6.6%, when the boom for the next five years was starting). CPI continues to be near double digits, and much higher than WPI (5.79%). Savings rate is not as high as it was in the boom, but purchases of gold should not be seen as necessarily unproductive. If loans are taken out against gold, as many entrepreneurs have been trying to popularize, the conventional modern financial system is not being fully bypassed. If not, then too it is simply a further squeezing of the monetary supply - and maybe the government can in that case consider adopting a dovish position with respect to the monetary base

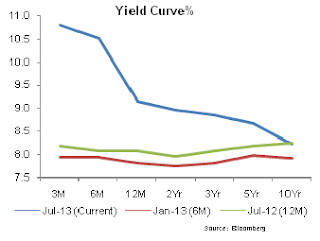

In any case, the CPI is disproportionately focused towards food prices, which in turn are influenced by - as the economist Surjit Bhalla informs us - by minimum support prices (MSPs), which have seen populist hikes above the usual norm in the last few years. This also suggests that containing inflation in such cases through monetary policy may be, on the margin, using a hammer instead of a scalpel. Raghuram Rajan, in a past academic life, has talked about inflation targeting. But in the real life he is as likely to cut rates before increasing them. Caught between a falling rupee, almost double digit inflation, and 4 odd percentage GDP growth and, of course, coming elections - the options are all bad, and the status quo with some minor adjustments is likely to prevail in the next half a year on the rates’ side. Rajan will be more influential initially on the regulatory and macro-prudential side, and could contribute well on innovation regarding financial inclusion public policy.

5. The J-Curve effect says that when a currency falls, the trade balance will first deteriorate before improving. It is possible that in India, while the imports will fall with a falling rupee but they are nonetheless more “sticky” or relatively inelastic (think petroleum demand etc.) while the exports (certainly manufacturing, even services) take some time to respond to a suddenly devalued currency. If true, this results in the J-curve effect for the trade balance, and the sudden weakeness in the rupee (in nominal terms) could lead to stronger exports and growth, other things being equal, in the coming quarter. In real terms (or measured by the Real Effective Exchange Rate), the rupee has actually not devalued that much against the USD because of the large inflation differentials between the two countries. Moreover, import restrictions and some capital account controls have been enforced – and while one may disagree with these from a long-term point of view, in the short term they will show results. Already, there are noises about the BPO industry getting a new lease of life in its competition with Phillippines etc, and the KPO and other industries also benefitting. For mass manufacturing exports to benefit though, we need labour and other reforms. Nonetheless, at least the import competition from China and Europe for local manufacturers – of everything from fans to heavy machines – has been substantially weakened. Watch out for stable imports and rising exports

These five reasons show that the pessimism has already been over-baked in the cake. But let us deconstruct the numbers a bit more. The latest sectoral quarterly growth (year-on-year) are as follows:

Personal and financial services have been doing great – and now with a weaker INR, will continue to do well (at least the export component, which is not a small element of services in India). The real problem is in mining and manufacturing – for which policy paralysis is directly to blame. The construction and trade/transportation heads also show that India is in the middle of a real estate slowdown, and the creaky infrastructure is not helping. A slow-motion property price burst could well be happening – at least in inflation adjusted terms. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) should take some solace from this, and the incoming governor Raghuram Rajan may be emboldened to marginally ease, going against the international grain of emerging markets such as Brazil. Moreover, as market commentator Deepak Shenoy rightly points out that if we use the CPI instead of WPI for the GDP deflator, we are already close to a recession, if not in one. The nominal growth of the economy in many large sectors has been single digit, while the CPI has been almost double-digit. This combined with the knowledge that India’s core inflation (sans food, energy) has been not that high could provide the intellectual justification for dovishness. On the other hand, no monetary policy is super-effective in India – there is the usual lag, but even the transmission mechanism is weak. Perhaps a tightening is what is in order, but the real responsibility (and its dereliction) has been because of the inability of the government to pass many competition-enhancing supply-side liberal reforms. While spending is also a real concern, India’s tax to GDP ratio remains low – and more importantly the debt to GDP ratio has been falling (although the debt service ratio is not that benign given rising interest rates)

*Contributed by Harsh Gupta; Economist from Darthmouth University, CFA & Professional Financial Consultant in Singapore (as on 2nd September 2013)